Austin Peay’s Amy Wright publishes new book that explores the ‘braided conversations’ of our lives

Dr. Amy Wright begins her new book, Paper Concert: A Conversation in the Round, with a quote: “For my students, who teach me how to ask.” What follows are nine essays pursuing the art of asking and the invisible links that connect one line of questioning to the next.

What Wright has done is invent a new form of essay writing, one that highlights subjects ranging from art, nature, sex and science She puts the scientists, artists and filmmakers she interviews in the spotlight.

“For years, I have conducted interviews for Zone 3,” Wright said. “I had well over 50 interviews by the time the writing started. I wanted to create a new form with the interviews. You’ve heard of flash nonfiction and flash fiction; well, I was doing a flash interview.”

A flash interview is often under 1,000 words and focused on one question. It is like flash nonfiction in that it is pithy while telling a complete and true story.

“I had a 100-page essay, essentially, that moved across all of these conversations, and wove them together,” Wright said.

This essay was published in the Georgia Review. Wright conducted additional interviews and added personal essays to double the length of the final book. In the final version, she structured the interviews to flow as one evolving conversation.

“Dorothy Allison might be talking about her family and her working class waitress mother. Then you’ve got David Baker talking about his father, who taught him about fishing and carpentry,” Wright said. “That’s the nature of the book: a braided conversation.”

‘It’s Always an Argument’

The book includes nine original essays by Wright beginning each chapter. Each chapter is a free-flowing conversation between many individuals about similar, and sometimes dissimilar, topics.

In the chapter titled “It’s Always an Argument,” Wright begins with an essay about arming herself with rocks to take on some school bus bullies and leads into a meditation on art’s purpose.

“Aesthetic work is impractical. To coil a thread of paper that will never spring to pin a shirt is not pragmatic, but it is not without purpose,” Wright writes.

She then loops the discussion into an interview she conducted with APSU Department of Art + Design Professor Emeritus Kell Black about his paper sculptures and the temporary nature of his work. Wright then wraps it all up into the story about the bus bullies. And that’s just the beginning of the chapter.

“I hope the prefatory personal essays that begin each chapter show how I think about the themes each contains,” Wright said. “Kell’s work inspired me to question the reasons we make art. Can art help us address social issues like climate change, racism or economic disparity? It can – as this book illustrates – when we talk to each other and share our stories.”

The ‘common touchstones’ of our conversations

In the opening of the essay “It’s Always an Argument,” Dorothy Allison, a writer who focuses on class struggle, feminism and lesbianism in South Carolina, says, “It’s always an argument, because class is defined in opposition, and to some extent in denial.”

Wright follows up by asking, “Why distinguish between the middle and working class when the top 10 percent of America’s wealthiest families hold 85 percent of the nation’s wealth?”

To which Allison responds, “When you find great artists and you query them you find out that they came from a small town, and they’re estranged from their family. You know why. Even if they weren’t queer, they’re queer in that broader context of being unacceptable.”

Wright then follows with a question she asked APSU alumnus Raven Jackson, a film director based in Tennessee: “What was it like to grow up Black and female at the beginning of the twenty-first century in Tennessee?”

To which Jackson echoes some of the same sentiments as Allison: “Growing up Black and as a Black woman, one of the most important lessons I’ve had to learn and relearn is how to take up space.”

This idea is further developed in the next entry, also by Allison: “Being despised is very hard to survive as a child, but once you don’t die you gain a kind of resilience.”

This back and forth, each entry seemingly responding to the one that came before, separated, in some cases, by many years and in different stages of Wright’s development as a writer, creates a dialogue that is timeless and eye-opening. The reader begins to realize halfway through that these wide-ranging questions and answers had common touchstones.

“I just like talking to people who are smart – artists, physicians, scientists, a wide range of people who aren’t normally interviewed,” Wright said. “The wisest among us don’t always have a platform. When we don’t consult them, we’re neglecting a valuable resource.”

Finding inspiration

Wright was inspired by Studs Terkel’s book Working, which Terkel describes as a book “about work” but also about “violence – to the spirit as well as the body. It is about ulcers as well as accidents, about shouting matches as well as fistfights, about nervous breakdowns as well as kicking the dog around. It is, above all (or beneath all), about daily humiliations. To survive the day is triumph enough for the walking wounded among the great many of us.”

Wright’s book is written in the same spirit.

“I loved Working,” she said. “It was something I read when I was in college when I was just becoming a journalist. It taught me that you can talk to people who aren’t authorities. You can talk to regular people who know stuff,” Wright said. “I’ve always had respect for what the average person has to say.”

While Wright interviews extraordinary people, they are asking the same questions the people in Terkel’s book are: How do we get through the day? Why do we go through the day? What’s waiting for us?

Dr. Wright has created a form in which this conversation can continue for all time – if we only take the time to see the connections between different perspectives.

To learn more

For more about program offerings from APSU’s Department of Languages and Literature, visit www.apsu.edu/langlit.

News Feed

View All News

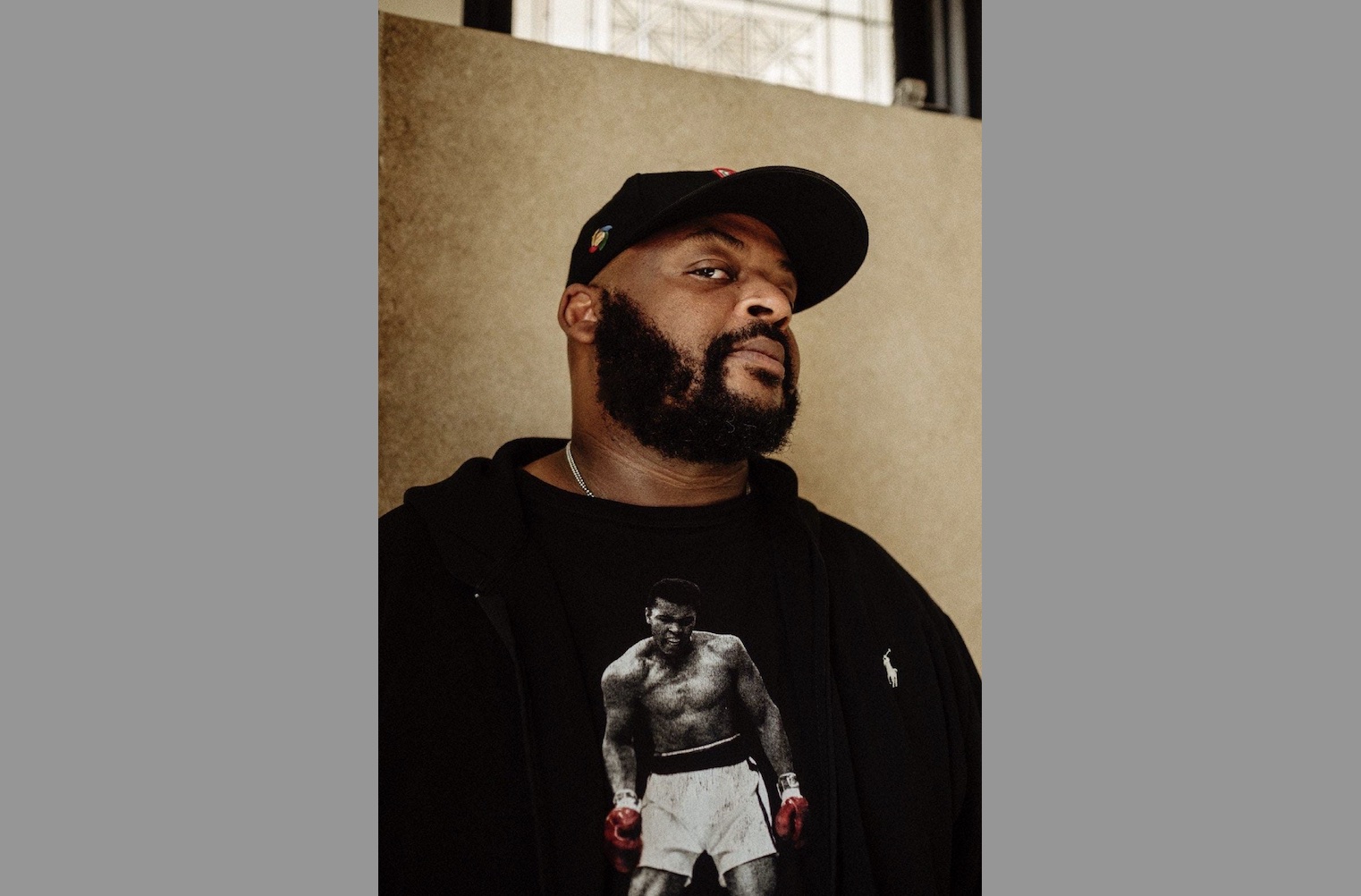

McArthur Genius Fellow and nationally acclaimed author Kiese Laymon will speak at Austin Peay State University at 7 p.m. on March 20, in the Mabry Concert Hall.

Read More

Austin Peay State University and JCPenney will host the fourth annual Suit-Up event on April 6, offering major discounts on professional attire for APSU students, faculty, staff, and alumni.

Read More

On each episode, listeners can expect to hear the latest news and announcements from the college, student spotlights, educational strategies and trends, and an interview with a featured guest.

Read More