APSU’s Thompson explores Tulsa Massacre reparations through national fellowship

CLARKSVILLE, Tenn. – Violet Fletcher is 107-years-old, but her memories of those days in 1921, when she was a 7-year-old living in Tulsa, Oklahoma, remain vivid.

“I still see Black men being shot, Black bodies lying in the street,” she testified earlier this year before Congress. “I still smell smoke and see fire. I still see Black businesses being burned. I still hear airplanes flying overhead. I hear the screams. I have lived through the massacre every day.”

Fletcher is the oldest living survivor of the 1921 Tulsa Massacre, and 100 years later, that city is still struggling with how to properly atone for the bloody violence that killed as many as 300 people and destroyed the affluent Greenwood district – known to many as Black Wall Street. Earlier this summer, the Urban Leaders Fellowship, a national social justice program that focuses on crafting policies at local and state government levels, developed a bold proposal for providing reparations to the survivors and their descendants, and one of the architects behind that proposal was Dr. James Thompson, associate dean of Austin Peay State University’s Eriksson College of Education.

“We proposed for the City of Tulsa to provide direct payments to the descendants,” Thompson said. “We also looked at how can we restore the mental health of the descendants, how can we restore the Greenwood District, how do we give the land back?”

The reparation plan includes providing grants for college tuition to descendants of the massacre and using publicly financed tax increment financing (TIF) to allow Black business owners to redevelop the Greenwood district that was taken from them.

Social Justice Fellowship

Last year, Thompson was among more than 1,200 scholars and public servants to apply for the competitive Urban Leaders Fellowship. Only 11 percent were selected to work on social justice projects across the country, and Thompson was among the very few given the task of examining the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Massacre.

“I worked with the Tulsa region for seven and a half weeks over the summer, and the primary part of the fellowship was to work on a social justice project,” he said. “I worked with two other members of the team, and we were asked to look at a social justice policy that looked at the Tulsa Massacre.”

Thompson’s team immediately went into research mode, analyzing how other communities responded to similar situations. They examined the Ocoee Massacre in Ocoee, Florida, where a white mob attacked Black residents trying to vote in the 1920 presidential election, and the Rosewood Massacre, which destroyed that predominately Black Florida town in 1923.

“We noticed that those two cities began to have what we call reparations through scholarships,” Thompson said. “A lot of the victims had passed away, but they were looking at the descendants of victims. Florida decided to give students scholarships. And it wasn’t just to direct descendants. If the direct descendants didn’t apply for the scholarship and they had extra funding that came from the state budget, anybody that was African America could apply for grant money to go to a public college in Florida.”

Thompson’s team also looked at the Jon Burge Torture Case. Burge, a former Chicago police commander, was sent to prison in 2011 for lying under oath, but according to the Chicago Sun-Times, “It’s believed that Burge and the detectives under his command tortured more than 100 people — mostly Black men — into giving false confessions from the 1970s to early 1990s.”

“The City of Chicago set up reparations to set up payment to victims of Jon Burge,” Thompson said. “They gave direct payments to the victims, and they set up scholarship funding for the victims and their descendants.”

Thompson’s team also noticed the city provided mental health care for the victims and their families. With that idea of restorative justice in mind, they began crafting a potential response to the Tulsa Massacre.

“In crafting and proposing this policy, we had to figure out how do we navigate the landmines because we know not everybody is going to be for payments,” Thompson said. “We saw how it worked for these other communities. In July, the City of Tulsa did apologize (for the 1921 massacre) but we wanted to extend the apology into action.”

Thompson and his team presented their work to their Urban Leaders Fellowship cohort, and they invited local politicians to hear the proposal. The City of Tulsa has not yet moved forward with the proposal.

The fellowship ended this summer, but Thompson is already looking at how he can apply it to his work at Austin Peay.

“This fellowship was set up for people who want to know more about social justice, learn more about how to craft good policy,” he said. “In order to impact change, you have to have good policies. At the University level, we can talk about the strategic plan and how do we craft our policies to meet those goals?”

For information on the fellowship, contact Thompson at thompsonjm@apsu.edu.

News Feed

View All News

Austin Peay State University welcomes Dr. Mitchell Cordova as its new provost and vice president for Academic Affairs, effective July 1. With over 27 years of higher education experience, Cordova joins Austin Peay from Florida Gulf Coast University, where he led significant improvements in student success and enrollment as vice president for Student Success and Enrollment Management.

Read More

Dr. Jackie Vogel and Dr. Catherine Haase plan to lead innovative Wintermester Study Away courses in Alaska later this year, offering opportunities in mathematics, cultural studies and wildlife ecology for STEM students.

Read More

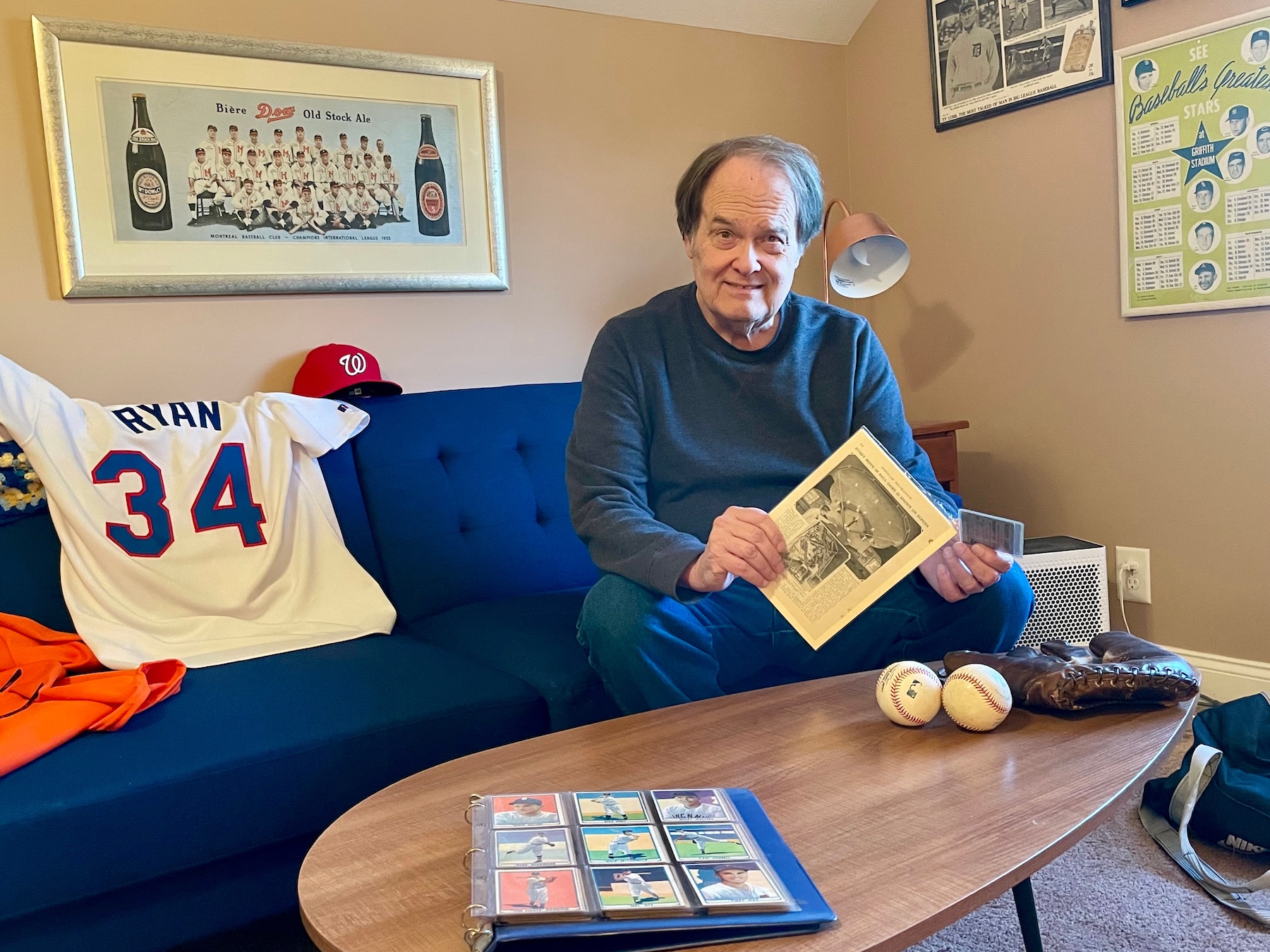

Adjunct professor and former Washington Nationals broadcaster Phil Wood uses his rare collection of baseball memorabilia, including a century-old Washington Auditorium pass, to bring America's pastime to life in the classroom.

Read More