Austin Peay, Fort Campbell partner in northern long-eared bat, white-nose syndrome study

(Posted Sept. 24, 2020)

Austin Peay State University’s Department of Biology is partnering with Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in an Intergovernmental Support Agreement (IGSA) to survey the base for endangered bat species. In the partnership, Fort Campbell provides funding for Dr. Catherine Haase, an assistant biology professor, three of her graduate students and their equipment.

“Once the land is surveyed, we will relay to Fort Campbell where the bats were found and what habitats they use,” Haase said. “Then Fort Campbell will make management decisions to conserve these areas. Austin Peay is providing the information in which these decisions will be made.”

Haase specializes in mammalian ecology. She is primarily interested in ecophysiology, which is the study of environmental conditions and how they affect mammalian behavior.

“My study species have ranged from moose in the Adirondack Mountains of New York, to grey wolves in Yellowstone National Park, to the Florida manatee in the Everglades,” Haase said.

The three-year partnership with Fort Campbell allows Haase and her team access to surveys of the Army post and the surrounding areas. The Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency provides permits for her team to trap members of the northern long-eared bat.

Tracking roosting behavior, bat diversity and disease effect

The project can be broken down into four main interests, on top of gathering information for Fort Campbell:

1. What trees bats are roosting in and how often they return to those trees.

2. The effect water quality and insect biomass has on bat diversity.

3. How white-nose syndrome affects reproductive patterns.

4. How white-nose syndrome affects what bats are thriving in the area.

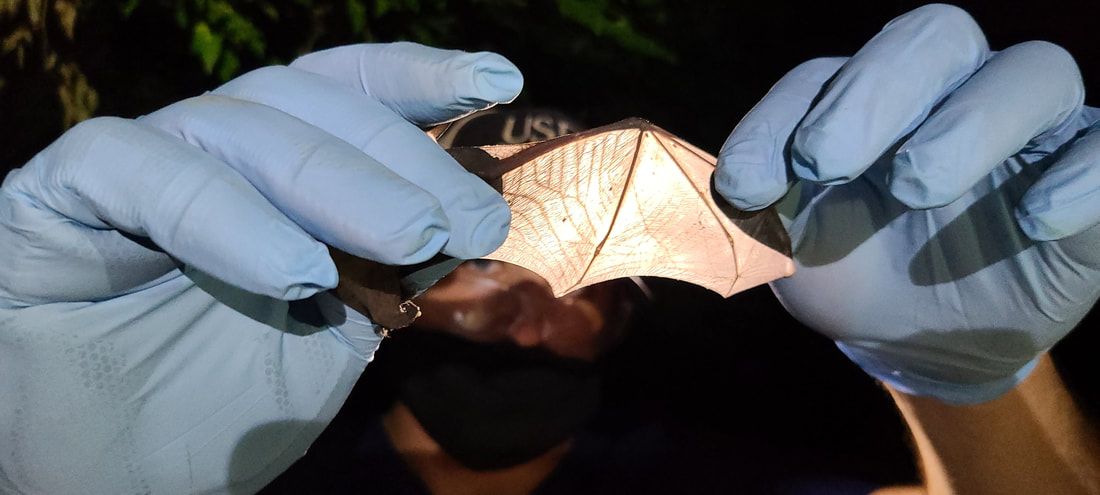

To do this, Haase and her team must net bats, document their physical traits and attach a transmitter that will allow them to track where the bats are going for 7-14 days. After that time, the signal is either lost or the transmitter falls off the bat.

“Bats use stream channels, roads and other types of corridors as flyways rather than fly throughout wooded areas,” Haase said. “We set up our nets across these channels for the highest probability of capture. Our nets are monofilament line that is very thin and therefore almost undetectable at night.

“The bats will fly right into the nets, get their wings caught and hang until we free them,” she added. “We check the nets every 10 minutes to prevent unneeded stress to the animal. If it is a certain species, such as the northern long-eared or tri-colored bat, we attach an armband to identify recaptured bats and attach a transmitter to track the bat. We then measure habitat characteristics of the roost tree.”

The most devastating disease

According to Haase, white-nose syndrome is “the most devastating disease any species has faced globally.”

Scientists have detected the disease across eastern and central North America and have evidence that it is moving west. The disease will become more prevalent in the coming years, Haase said.

White-nose syndrome is a fungus that grows on the wings and nose of the bat, deteriorating the barrier to water loss which causes hibernating bats to arouse from hibernation to replenish. Arousing burns fat that bats have accumulated prior to hibernation.

“The bats get dehydrated more quickly and thus need to arouse more frequently,” she said. “These more frequent arousals cause the bats to burn through all their winter fat, and they essentially starve to death before the hibernation season is complete.”

Bats are natural “insectivores,” meaning they feed only on insects, Haase said. A lot of their diet consists of agricultural pests. Bats provide “as much as $20 billion savings globally in pest control,” she said. They are also important pollinators.

White-nose syndrome also can affect reproduction. Bats do not reproduce until certain physiological requirements are met. Female bats infected with the disease may postpone reproduction, decreasing the amount of time baby bats (pups) have to fatten themselves up to survive hibernation. It is a vicious cycle of using too much of their food supply and not having enough time in the spring to meet the necessary caloric intake.

Work would be impossible without Fort Campbell

Partnering with Fort Campbell has allowed Haase and her team to do their part in helping native bats survive the pandemic.

“Fort Campbell has been great in coordinating equipment and site access,” Haase said. “Our work would be impossible to do without their funding for equipment and their site information.”

Haase hopes to partner with Fort Campbell in the future. Other bat species, such as the tri-colored bat, are under consideration for federal protection. However, the government needs more data to determine if that is necessary.

“If they get listed, then there will be specific compliance efforts required by state and federal agencies if one of these species is found on their property,” Haase said. “If the tri-colored bat becomes an Endangered Species Agency-listed species, Fort Campbell may be required to do surveys such as this in the future, which would be a great opportunity for this partnership to continue.”

To learn more

- • For more about Dr. Haase’s bat research, visit https://www.haaseecolab.com/ or follow @HaaseEcoLab on Twitter.

- • For more about Austin Peay’s Department of Biology, go to https://www.apsu.edu/biology/.

News Feed

View All News

This year's event will feature performances by the Maharajah Flamenco Trio, Colin Isotti, McKelvey Duo, Juanito Pascual, and Montrose Duo from March 16-19.

Read More

IRS-certified volunteers from APSU are helping community members prepare their taxes as part of a service learning class offered through the College of Business.

Read More

Dr. Isaac Sitienei, an associate professor in APSU's Department of Agriculture, will discuss how artificial intelligence is shaping the agriculture industry at the next Science on Tap.

Read More